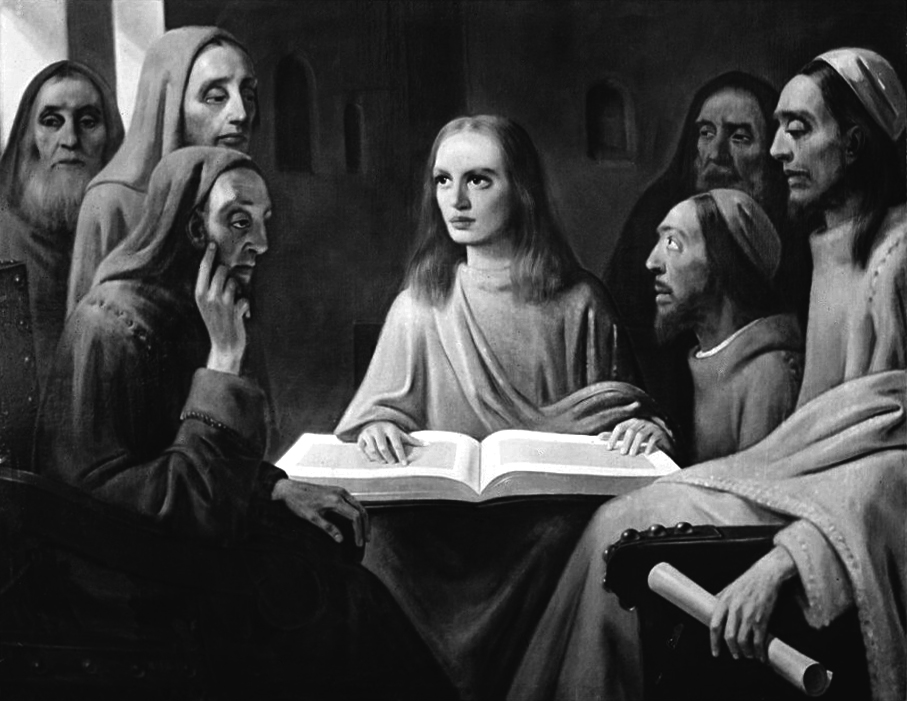

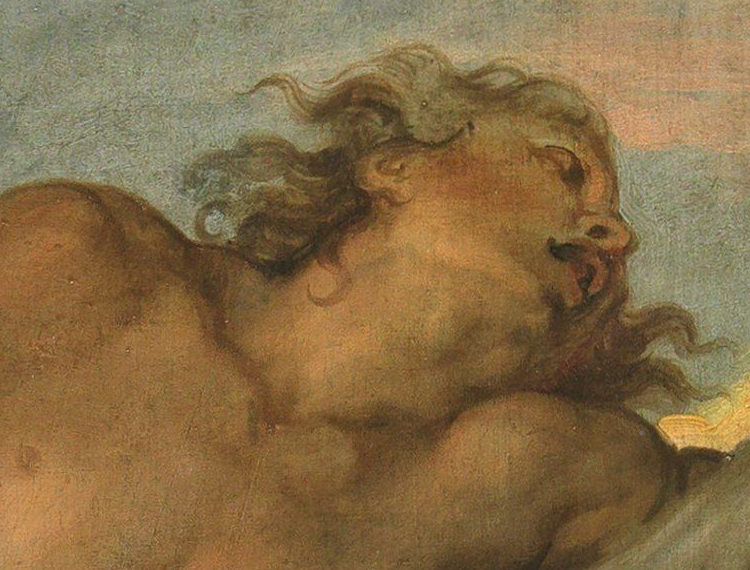

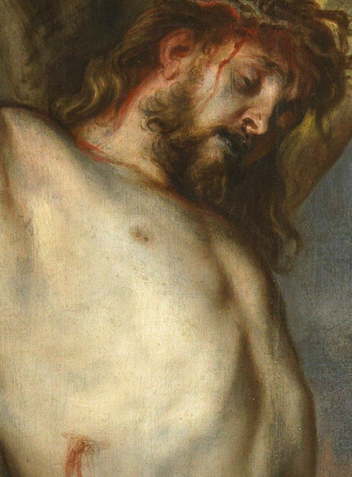

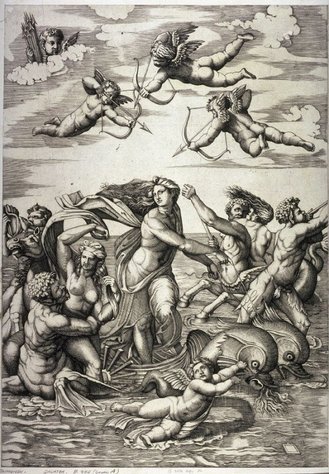

Historically, still life has occupied a pretty lowly position. It doesn’t aim to tell big complex human stories like a history painting, it doesn’t even show one human story like a portrait, nor the emotive space of a landscape. It shows a bunch of stuff essentially, the human element notable by its absence, though that is sometimes implied. It’s often part of an artist’s training, and so seen as elementary, simple, basic. All that is generally true and yet I find myself drawn to it.

The humility of the genre is precisely why I like it. The drama of a history painting, for all its sophistication, is removed from our daily lived experience. In many ways that is the point of it. Currently I am much more interested in pictures which find meaning, beauty, and poetry in the everyday.

The humility of the genre is precisely why I like it. The drama of a history painting, for all its sophistication, is removed from our daily lived experience. In many ways that is the point of it. Currently I am much more interested in pictures which find meaning, beauty, and poetry in the everyday.

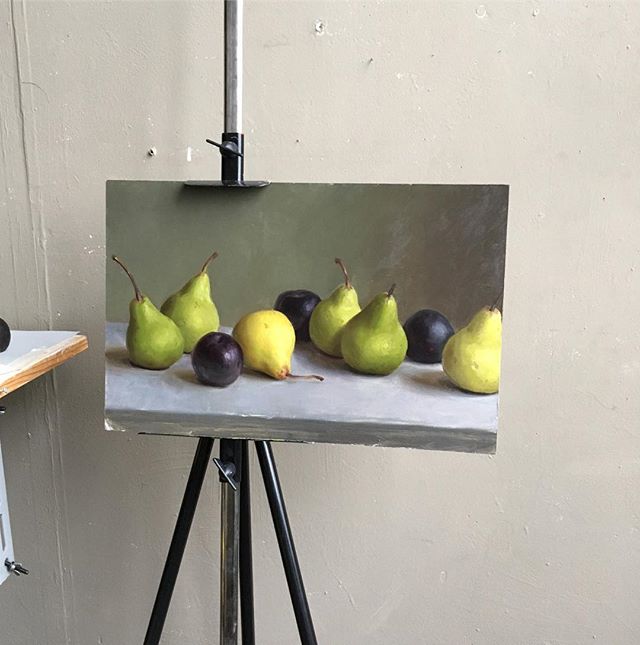

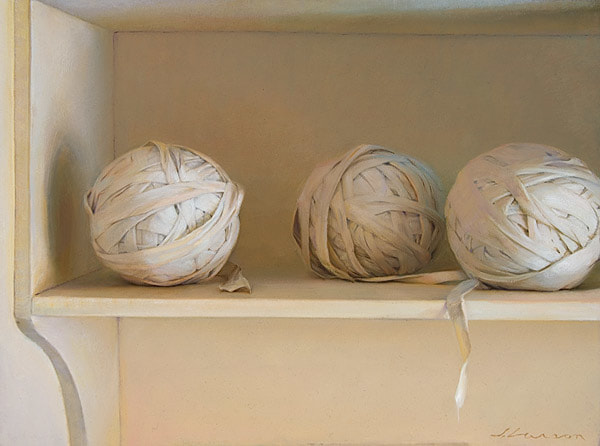

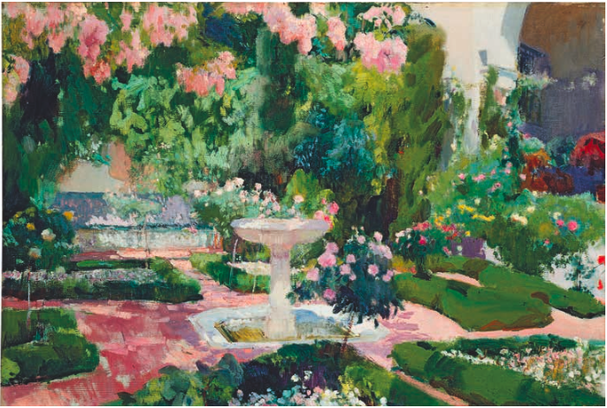

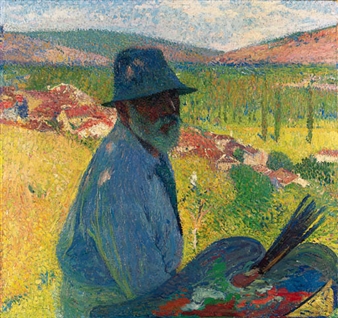

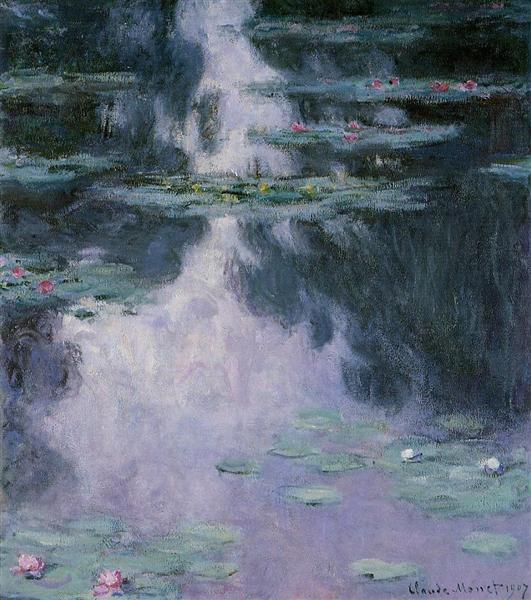

To slow down and spend time observing a few objects is a wonderful privilege: Exploring the interaction of abstract shapes and colours, becoming attuned to the subtle play of light, delighting in the peculiarities of specific forms. Still life doesn’t communicate a message or meaning, but rather holds meaning in an open-handed sort of way. They are meditations not polemics. Whether the objects themselves suggest some associated memory, or the light suggests some associated mood, the still lifes I like tend to be very open to the viewer bringing meaning to the picture. I’ve never responded well to still life which does the opposite, trying to tell the viewer the meaning, such as Baroque still lifes designed to display wealth, or symbolic images whose iconography one must decode.

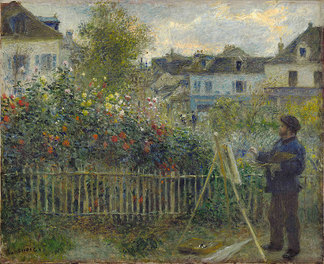

There are numerous masters of the genre to be found in great museums: Claesz, Chardin, Fantin-Latour, Cezanne etc. But I want to focus on contemporary painters in this post. Below are a handful of still lifes by contemporary painters which I love.

There are numerous masters of the genre to be found in great museums: Claesz, Chardin, Fantin-Latour, Cezanne etc. But I want to focus on contemporary painters in this post. Below are a handful of still lifes by contemporary painters which I love.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed